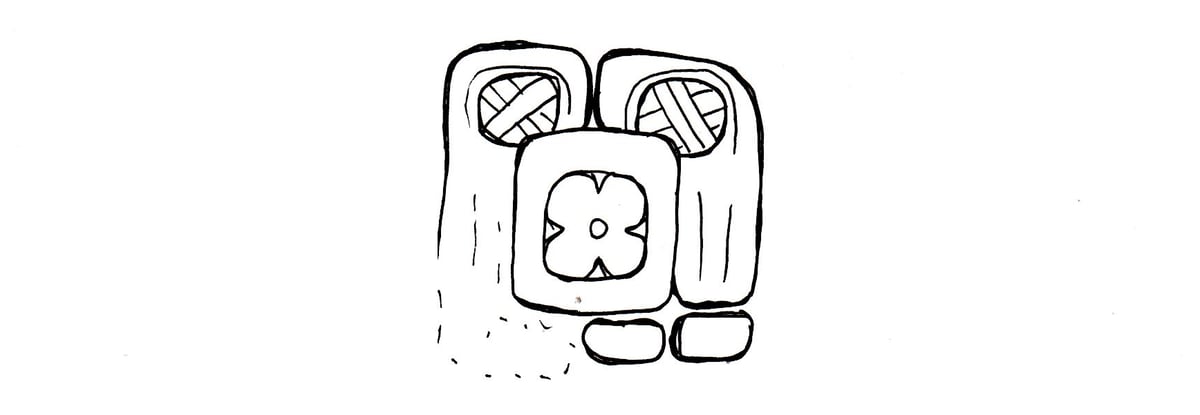

This morning I mentioned to Jason that I was still thinking about the Mayan calendar/Julian calendar overlap thing — did both cultures really record the same solar eclipse?! — and how mind-blowing it is to even contemplate. We then talked about how crazy it must have been to live back then (in 790 AD) and see the sun just casually disappear, etc.

And then I was wondering: What’s happening now that people living in the year 3200 will pity us for not understanding? “Wow, can you imagine living back then and not knowing exactly how [viruses appear/cancer strikes/the Voynich Manuscript came into existence]? Or precisely what happened at Dyatlov Pass, or on board the Mary Celeste?” (Okay now I’m just googling “mysteries.”) Anyway, I’m not high, I swear. But please chime in if anything comes to mind. “It must have been so weird to not know what dogs were saying.”

Years, days, seasons, even months correspond to natural divisions of time in most parts of the Earth. We split those into hours, minutes, seconds, pretty cleanly if you’re a post-Sumerian who loves the number 60. But weeks? You can talk about phases of the moon, but for the most part, weeks are our most arbitrary (and mathematically awkward) imposition on the experience of time. (Not everybody observes a seven-day week, even today.)

So how did we make the week a thing?

Although taboos and cosmologies in several different cultures attached significance to seven-day cycles much earlier, there is no clear evidence of any society using such cycles to track time in the form of a common calendar before the end of the 1st century CE. As the scholars Ilaria Bultrighini and Sacha Stern have recently documented, it was in the context of the Roman Empire that a standardised weekly calendar emerged out of a combination and conflation of Jewish Sabbath counts and Roman planetary cycles. The weekly calendar, from the moment of its effective invention, reflected a union of very different ways of counting days. This fact alone ought to discourage us from assuming that weeks have just one obvious technological application.

Along with charting the stars and setting aside time for the sacred, weeks, David Henkin argues, serve as mnemonic devices, divide work from non-work days, allow us to distinguish one cycle of days from the next, and offer a regular opportunity to take stock.

Starting around the nineteenth century, particularly in the United States, the division of time into weeks (which correspondingly creates a repeating order of days) also allowed for a new, industrial-bureaucratic conditioning to take place: we created schedules.

Increasingly and pervasively, Americans were applying the technology of the seven-day count to the project of scheduling. Some of these schedules emerged in work settings, specifically schools and housekeeping. As daily school attendance became a normative activity outside the southern US in the early 19th century, masses of schoolchildren learned early and often to expect certain regular activities (examinations, early recesses, special classes) to take place on the same day of the week. And as new norms of hygiene and respectability took hold in middle-class households, domestic manuals began prescribing weekly schedules for core housekeeping tasks: washing on Mondays, ironing on Tuesdays, baking on Wednesdays.

Offices and workplaces were soon to follow. Eventually, the week provided such a regular structure to our days and activities that when any disruption happens (be it mild and passing like a holiday, or more deeply deranging, like a pandemic), it throws us into disorientation. We made the week, but now we can’t live without it.

I love James Joyce’s Ulysses, spent a huge chunk of my life in grad school trying to figure out that book, still follow a ton of modernist scholars and Joyce freaks on social media, and even I managed to forget that today was Bloomsday, the anniversary of Stephen Dedalus and Leopold and Molly Bloom’s treks across Dublin in that book.

I also love Star Trek: The Next Generation, probably even more than I do James Joyce, and I had no idea that today was also “Captain Picard’s Day,” when the children on the Enterprise honor him (and make him deeply uncomfortable) by presenting him with arts and crafts.

What I needed (for a peculiar definition of “need”) was a calendar plugin, something to put the anniversary of Terminator 2’s Judgment Day, The Simpsons’ Whacking Day, and Roy Batty’s inception date directly into my stream of doctor’s appointments, scheduled phone calls, NBA games shown on broadcast basic cable, and Facebook friends’ birthdays.

And that’s exactly what the staff at Atlas Obscura made: a pop culture calendar of imaginary holidays. It doesn’t solve real problems, unless those problems include properly commemorating The Purge. But it is pretty fun.

Stay Connected