Why humans need stories

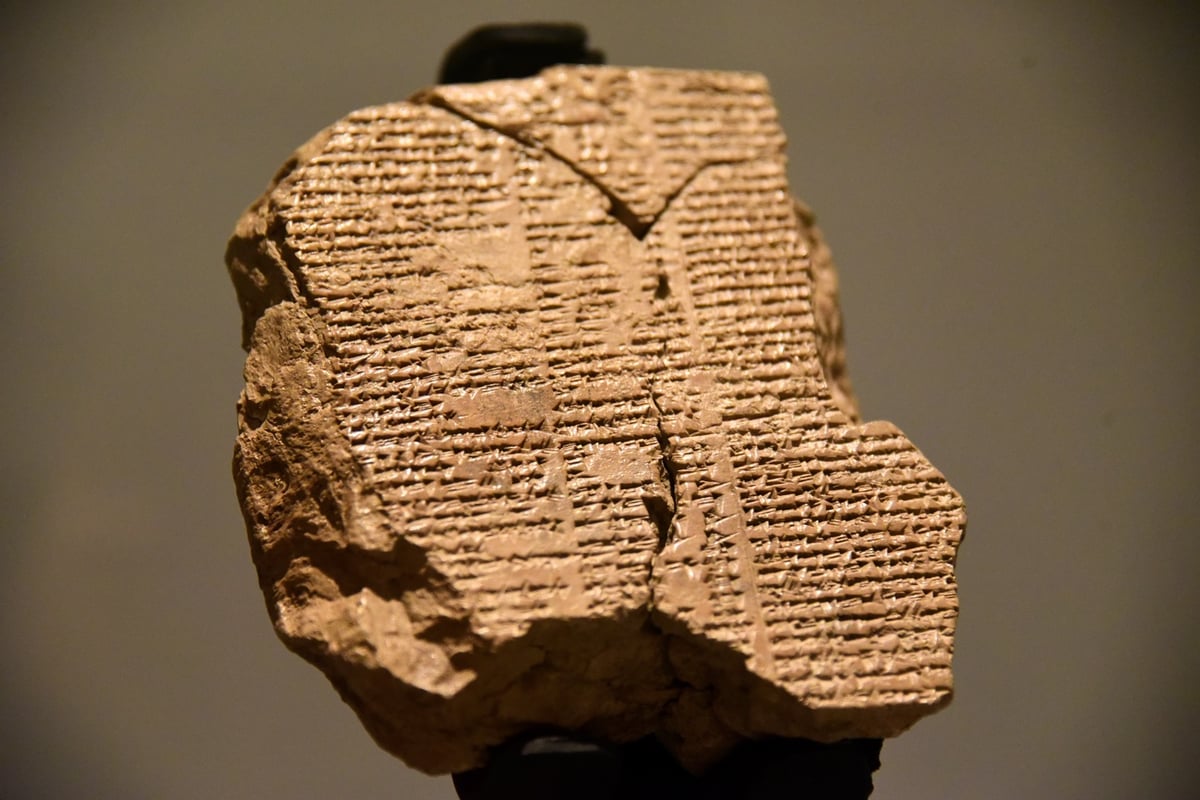

There’s a tendency these days to disregard the idea of “storytelling.” Like so many terms it’s been overused, its meaning stretched to within an inch of its life. We watch a lot of Netflix and obsess over some stories in the news but we don’t read as many books and we don’t gather around the fire to tell stories so much. But they have been part of our lives forever. In Our fiction addiction: Why humans need stories, the author takes us through some of the oldest stories we tell and why evolutionary theorists are studying them.

One common idea is that storytelling is a form of cognitive play that hones our minds, allowing us to simulate the world around us and imagine different strategies, particularly in social situations. “It teaches us about other people and it’s a practice in empathy and theory of mind,” says Joseph Carroll at the University of Missouri-St Louis. […]

Providing some evidence for this theory, brain scans have shown that reading or hearing stories activates various areas of the cortex that are known to be involved in social and emotional processing, and the more people read fiction, the easier they find it to empathise with other people. […]

Crucially, this then appeared to translate to their real-life behaviour; the groups that appeared to invest the most in storytelling also proved to be the most cooperative during various experimental tasks - exactly as the evolutionary theory would suggest. […]

By mapping the spread of oral folktales across different cultural groups in Europe and Asia, some anthropologists have also estimated that certain folktales - such as the Faustian story of The Smith and the Devil - may have arrived with the first Indo-European settlers more than 6,000 years ago, who then spread out and conquered the continent, bringing their fiction with them.

The author also says this; “Although we have no firm evidence of storytelling before the advent of writing.” He then goes on to write about the paintings in Lascaux which seem to be telling stories, so he’s aware of some examples. Randomly today I also happened on this about Australia’s ancient language shaped by sharks which talks about the beautiful history of the Yanyuwa people and their relationship with the tiger shark. They’ve been “dreaming,” telling stories, for 40,000-years!

This forms one of the oldest stories in the world, the tiger shark dreaming. The ‘dreaming’ is what Aboriginal people call their more than 40,000-year-old history and mythology; in this case, the dreaming describes how the Gulf of Carpentaria and rivers were created by the tiger shark.

And then there’s this incredible aspect of their culture:

What’s especially unusual about Yanyuwa is that it’s one of the few languages in the world where men and women speak different dialects. Only three women speak the women’s dialect fluently now, and Friday is one of few males who still speaks the men’s. Aboriginal people in previous decades were forced to speak English, and now there are only a few elderly people left who remember the language.

Stay Connected