Monk Hacks: Dealing With Distraction in Late Antiquity

For monks, concentration wasn’t just a practical necessity, but a spiritual discipline. Consequently, they spent a lot of time thinking about the nature of distraction and how to fight it.

Sometimes [monks] accused demons of making their minds wander. Sometimes they blamed the body’s base instincts. But the mind was the root problem: it is an inherently jumpy thing. John Cassian, whose thoughts about thinking influenced centuries of monks, knew this problem all too well. He complained that the mind ‘seems driven by random incursions’. It ‘wanders around like it were drunk’. It would think about something else while it prayed and sang. It would meander into its future plans or past regrets in the middle of its reading. It couldn’t even stay focused on its own entertainment - let alone the difficult ideas that called for serious concentration.

That was in the late 420s. If John Cassian had seen a smartphone, he’d have forecasted our cognitive crisis in a heartbeat.

Actually, I can think of several other things John Cassian would have done if he had seen a smartphone, but let’s not get off track. Sure. He’d have figured out we’d have some problems.

Here’s a paradox: monks and nuns weren’t all about that austerity, at least cognitively. Instead, they’d go full tilt into embracing the wild, distracting powers of the mind, but trying to harness them for useful purposes.

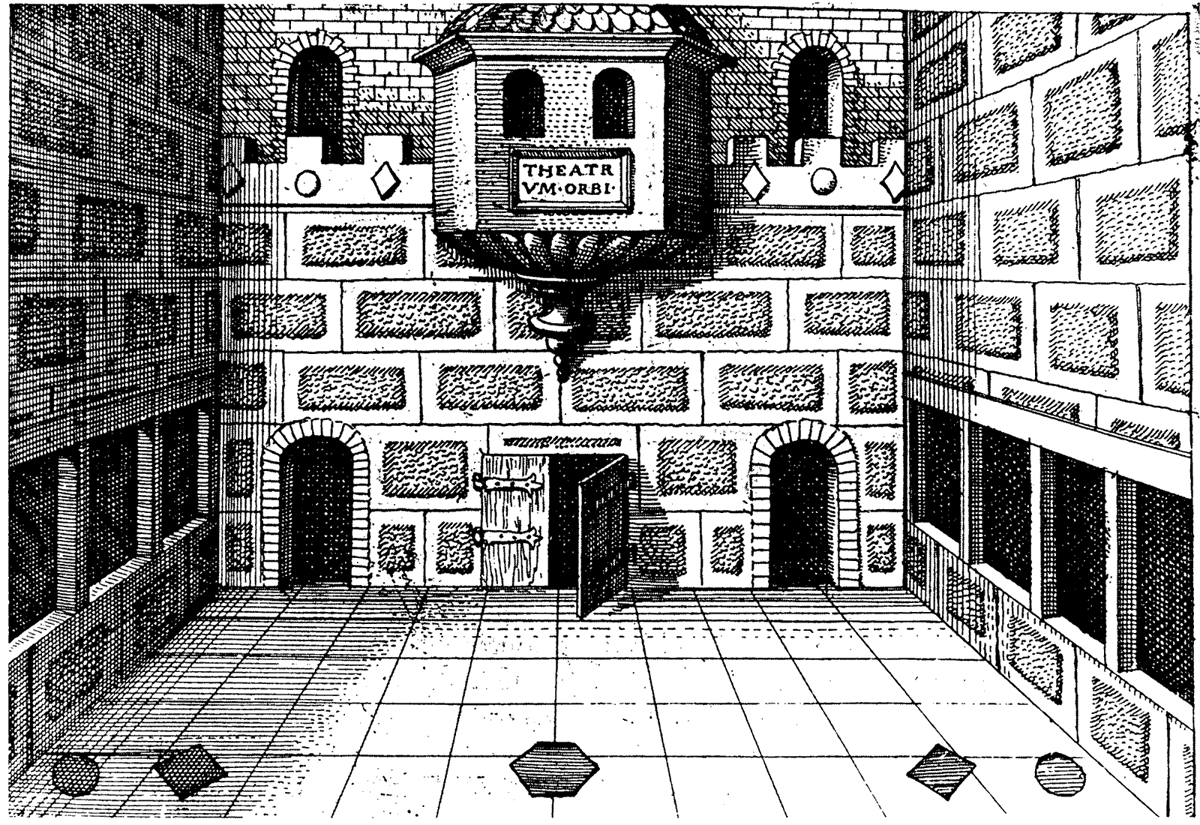

Part of monastic education involved learning how to form cartoonish cognitive figures, to help sharpen one’s mnemonic and meditative skills. The mind loves stimuli such as colour, gore, sex, violence, noise and wild gesticulations. The challenge was to accept its delights and preferences, in order to take advantage of them. Authors and artists might do some of the legwork here, by writing vivid narratives or sculpting grotesque figures that embodied the ideas they wanted to communicate. But if a nun wanted to really learn something she’d read or heard, she would do this work herself, by rendering the material as a series of bizarre animations in her mind. The weirder the mnemonic devices the better - strangeness would make them easier to retrieve, and more captivating to think with when she ‘returned’ to look them over.

My favorite book about this is Francis Yates’s The Art of Memory; it’s more about the Renaissance than the height of the monastic period, but focuses on the history and artistry of these various mnemonic devices, while doubling as a kind of cultural history of the mind.

Stay Connected