Nabokov’s dreams

Lately, I’ve been getting more and more interested in dreams, as experiences and as psychological phenomena. I don’t have a fancy theory of dreams as yet beyond “brain garbage,” but brain garbage is still a pretty interesting idea.

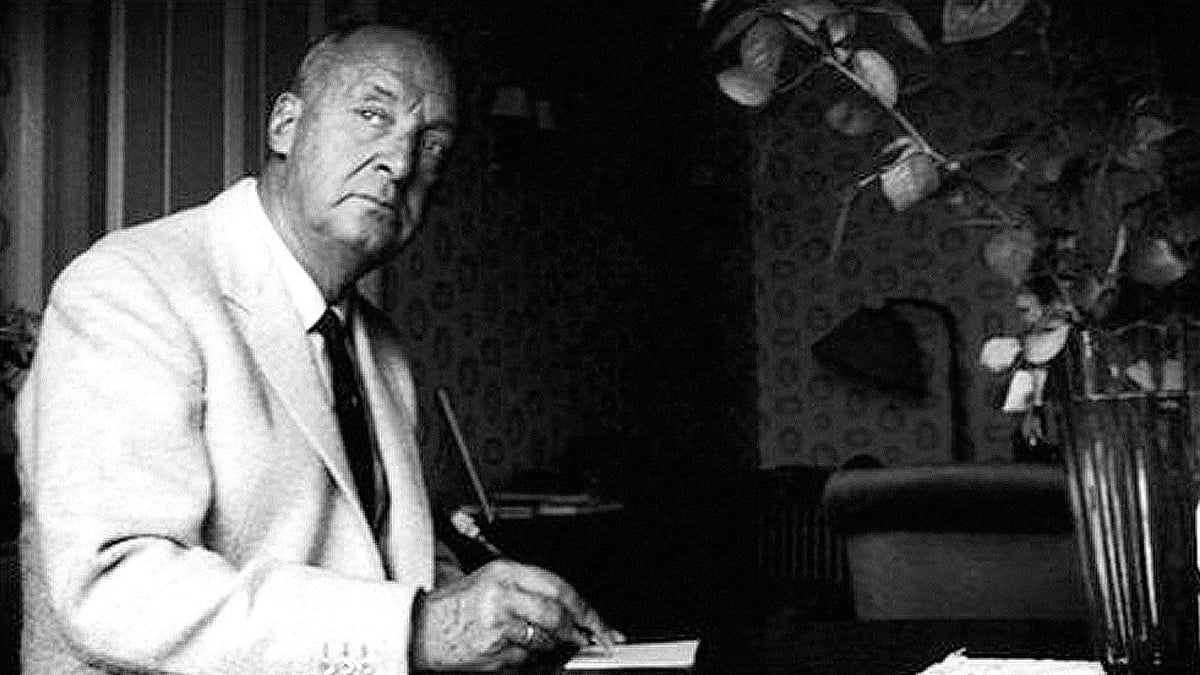

A British writer named JW Dunne, writing in the 1920s, did have a fancy theory of dreams — he thought they were a way to access a different kind of consciousness of time, giving clues to precognition and all sorts of other metaphysical leaps. And Dunne’s philosophies appealed to many writers, including Vladimir Nabokov, who kept records of his dreams on neat stacks of index cards. (Nabokov loved index cards.)

Though he kept up his index-card routine for eighty nights, [Nabokov] drifted from Dunne’s method. Rather than flagging his dreams for their precognitive potential, he began to find patterns among them, breaking them into categories: nostalgic or erotic, shaped by current events or professional anxieties. Apart from a dry spell he referred to as “dream constipation,” Nabokov was a prodigious dreamer, his mind a wellspring of trenchant, tender, and perturbing images that he recounts with verve. An old Cambridge classmate “gloomily consumes a thick red steak, holding it rather daintily, the nails of his long fingers glisten[ing] with cherry-red varnish.” A cryptic caller “wonders how I knew she was Russian. I answer dream-logically that only Russian women speak so loud on the phone.” There are capers: in one, Nabokov and his son, Dmitri, “are trying to track down a repulsive plump little boy who has killed another child—perhaps his sister.” And there are intimations of mortality: “A tremendous very black larch paradoxically posing as a Christmas tree completely stripped of its toys, tinsel, and lights, appeared in its abstract starkness as the emblem of permanent dissolution.”

Nabokov’s dream thinking found its apex in the novel Ada, where he writes, “What are dreams? A random sequence of scenes, trivial or tragic, viatic or static, fantastic or familiar, featuring more or less plausible events patched up with grotesque details, and recasting dead people in new settings.” Dreams are “tricks of an agent of Chronos… Some law of logic should fix the number of coincidences, in a given domain, after which they cease to be coincidences, and form, instead, the living organism of a new truth.”

Stay Connected